From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the novella. For other uses, see Flatland (disambiguation).

| Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions | |

|---|---|

The cover to Flatland, 6th Edition. | |

| Author(s) | Edwin A. Abbott |

| Illustrator | Edwin A. Abbott |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Novella |

| Publisher | Seely & Co. |

| Publication date | 1884 |

| Pages | viii, 100 pp |

| ISBN | N/A |

| OCLC Number | 2306280 |

| LC Classification | QA699 |

| Read online | Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions at Wikisource |

Several films have been made from the story, including a feature film in 2007 called Flatland. Other efforts have been short or experimental films, including one narrated by Dudley Moore and a short film with Martin Sheen titled Flatland: The Movie.

Contents |

[edit] Plot

The story is about a two-dimensional world referred to as Flatland which is occupied by geometric figures. Women are simple line-segments, while men are regular polygons with various numbers of sides. The narrator is a humble square, a member of the social caste of gentlemen and professionals in a society of geometric figures, who guides us through some of the implications of life in two dimensions. The Square has a dream about a visit to a one-dimensional world (Lineland) which is inhabited by "lustrous points". He attempts to convince the realm's ignorant monarch of a second dimension but finds that it is essentially impossible to make him see outside of his eternally straight line.He is then visited by a three-dimensional sphere, which he cannot comprehend until he sees Spaceland for himself. This Sphere (who remains nameless, like all characters in the novella) visits Flatland at the turn of each millennium to introduce a new apostle to the idea of a third dimension in the hopes of eventually educating the population of Flatland of the existence of Spaceland. From the safety of Spaceland, they are able to observe the leaders of Flatland secretly acknowledging the existence of the sphere and prescribing the silencing of anyone found preaching the truth of Spaceland and the third dimension. After this proclamation is made, many witnesses are massacred or imprisoned (according to caste).

After the Square's mind is opened to new dimensions, he tries to convince the Sphere of the theoretical possibility of the existence of a fourth (and fifth, and sixth ...) spatial dimension. Offended by this presumption and incapable of comprehending other dimensions, the Sphere returns his student to Flatland in disgrace.

The Square then has a dream in which the Sphere visits him again, this time to introduce him to Pointland. The point (sole inhabitant, monarch, and universe in one) perceives any attempt at communicating with him as simply being a thought originating in his own mind (cf. Solipsism):

The Square recognizes the connection between the ignorance of the monarchs of Pointland and Lineland with his own (and the Sphere's) previous ignorance of the existence of other, higher dimensions.'You see,' said my Teacher, 'how little your words have done. So far as the Monarch understands them at all, he accepts them as his own – for he cannot conceive of any other except himself – and plumes himself upon the variety of Its Thought as an instance of creative Power. Let us leave this God of Pointland to the ignorant fruition of his omnipresence and omniscience: nothing that you or I can do can rescue him from his self-satisfaction.'[2]— the Sphere

Once returned to Flatland, the Square finds it difficult to convince anyone of Spaceland's existence, especially after official decrees are announced – anyone preaching the lies of three dimensions will be imprisoned (or executed, depending on caste). Eventually the Square himself is imprisoned for just this reason, where he spends the rest of his days attempting to explain the third dimension to his brother.

[edit] Social elements

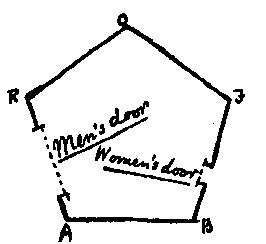

Men are portrayed as polygons whose social status is determined by their regularity and the number of their sides with a Circle considered to be the "perfect" shape. On the other hand, females consist only of lines and are required by law to sound a "peace-cry" as they walk, because when a line is coming towards an observer in a 2-D world, her body appears merely as a point. The Square evinces accounts of cases where women have accidentally or deliberately stabbed men to death, as evidence of the need for separate doors for women and men in buildings.In the world of Flatland, classes are distinguished using the "Art of Hearing," the "Art of Feeling" and the "Art of Sight Recognition." Classes can be distinguished by the sound of one's voice, but the lower classes have more developed vocal organs, enabling them to feign the voice of a polygon or even a circle. Feeling, practised by the lower classes and women, determines the configuration of a person by feeling one of their angles. The "Art of Sight Recognition," practised by the upper classes, is aided by "Fog," which allows an observer to determine the depth of an object. With this, polygons with sharp angles relative to the observer will fade out more rapidly than polygons with more gradual angles. Colour of any kind was banned in Flatland after Isosceles workers painted themselves to impersonate noble Polygons. The Square describes these events, and the ensuing war, at length.

The population of Flatland can "evolve" through the "Law of Nature", which states: "a male child shall have one more side than his father, so that each generation shall rise (as a rule) one step in the scale of development and nobility. Thus the son of a Square is a Pentagon, the son of a Pentagon, a Hexagon; and so on."

This rule is not the case when dealing with isosceles triangles (Soldiers and Workmen) with only two congruent sides. The smallest angle of an isosceles triangle gains thirty arc minutes (half a degree) each generation. Additionally, the rule does not seem to apply to many-sided polygons. For example, the sons of several hundred-sided polygons will often develop fifty or more sides more than their parents. Furthermore, the angle of an isosceles triangle or the number of sides of a (regular) polygon may be altered during life by deeds or surgical adjustments.

An equilateral Triangle is a member of the craftsman class. Squares and Pentagons are the "gentlemen" class, as doctors, lawyers, and other professions. Hexagons are the lowest rank of nobility, all the way up to (near) circles, who make up the priest class. The higher-order polygons have much less of a chance of producing sons, preventing Flatland from being overcrowded with noblemen.

Regular polygons were considered in isolation until chapter seven of the book when the issue of irregularity, or physical deformity, became considered. In a two dimensional world a regular polygon can be identified by a single angle and/or vertex. In order to maintain social cohesion, irregularity is to be abhorred, with moral irregularity and criminality cited, "by some" (in the book), as inevitable additional deformities, a sentiment with which the Square concurs. If the error of deviation is above a stated amount, the irregular polygon faces euthanasia; if below, he becomes the lowest rank of civil servant. An irregular polygon is not destroyed at birth, but allowed to develop to see if the irregularity could be “cured” or reduced. If the deformity could not be corrected then the irregular should be “painlessly and mercifully consumed.”[3]

[edit] Flatland as a social satire

In Flatland Abbott describes a society rigidly divided into classes. Social ascent is the main aspiration of its inhabitants, apparently granted to everyone but in reality strictly controlled by the few that are already positioned at the top of the hierarchy. Freedom is despised and the laws are cruel. Innovators are either imprisoned or suppressed. Members of lower classes who are intellectually valuable, and potential leaders of riots, are either killed or corrupted by being promoted to the upper classes. The organisation and government of 'Flatland' is so self-satisfied and perfect that every attempt or change is considered dangerous and harmful. This world, as ours, is not prepared to receive 'Revelations from another world'.The satirical part is mainly concentrated in the first part of the book, 'This World', which describes Flatland. The main points of interest are the Victorian concept on women's roles in the society and in the class-based hierarchy of men.[4]

Abbott has been accused of misogyny due to his portrait of women in 'Flatland'. In his Preface to the Second and Revised Edition, 1884, he answers such critics by stating that the Square:

was writing as a Historian, he has identified himself (perhaps too closely) with the views generally adopted by Flatland and (as he has been informed) even by Spaceland, Historians; in whose pages (until very recent times) the destinies of Women and of the masses of mankind have seldom been deemed worthy of mention and never of careful consideration.—the Editor

[edit] Critical reception

Although Flatland was not ignored when it was published,[5] it did not obtain a great success. Proof of that can be considered the fact that in the entry on Edwin Abbott Abbott in the Dictionary of National Biography, Flatland is not even mentioned.[6]The book was discovered again after Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity was published, which introduced the concept of a fourth dimension. Flatland was mentioned in a letter entitled "Euclid, Newton and Einstein" published in Nature on February 12, 1920. In this letter Abbott is depicted, in a sense, as a prophet due to his intuition of the importance of time to explain certain phenomena:[6][7]

Some thirty or more years ago a little jeu d'esprit was written by Dr. Edwin Abbott entitled Flatland. At the time of its publication it did not attract as much attention as it deserved... If there is motion of our three-dimensional space relative to the fourth dimension, all the changes we experience and assign to the flow of time will be due simply to this movement, the whole of the future as well as the past always existing in the fourth dimension. —from a "Letter to the Editor" by William Garnett. in Nature on February 12, 1920.

[edit] Editions in print

- Flatland (5th edition, 1963), 1983 reprint with foreword by Isaac Asimov, HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-463573-2

- bound together back-to-back with Dionys Burger's Sphereland (1994), HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-273276-5

- The Annotated Flatland (2002), coauthor Ian Stewart, Perseus Publishing, ISBN 0-7382-0541-9

- Signet Classics edition (2005), ISBN 0-451-52976-6

- Oxford University Press (2006), ISBN 0-19-280598-3

- Dover Publications thrift edition (2007), ISBN 0-486-27263-X

- CreateSpace edition (2008), ISBN 1-4404-1778-4

[edit] Related works

- Numerous imitations or sequels to Flatland have been written, including: An Episode on Flatland: Or How a Plain Folk Discovered the Third Dimension by Charles Howard Hinton (1907), Sphereland by Dionys Burger (1965), The Planiverse by A. K. Dewdney (1984), Flatterland by Ian Stewart (2001), and Spaceland by Rudy Rucker (2002). Short stories inspired by Flatland include The Incredible Umbrella by Marvin Kaye (1980), Message Found in a Copy of "Flatland" by Rudy Rucker (1983), and The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics by Norton Juster (1963).

- Flatland (1965), an animated short film based on the novella, directed by Eric Martin and based on an idea by John Hubley. The film uses the voice of Dudley Moore and other actors from the comedy group Beyond the Fringe.[8] [9] [10]

- Flatland (2007), a 98-minute animated independent feature film version directed by Ladd Ehlinger Jr,[11] which updates the satire from Victorian England to the modern-day United States (e.g. with a "president" instead of a "king", advanced technology in Spaceland, etc.).[12]

- Flatland: The Movie (2007) by Dano Johnson & Jeffrey Travis,[13] a 30-minute animated educational film with the voices of Martin Sheen, Kristen Bell, Michael York, and Tony Hale.

- In an episode of Cosmos, Carl Sagan discusses Flatland as an analogy to explain other dimensions other than our three physical dimensions.

- "Behold, Eck!", an episode of the original The Outer Limits series, is freely inspired from Flatland; it features a friendly, endearing alien creature named Eck, coming from a two-dimensional reality, trapped into our own three dimensions after a miscalculation during the crossing of a time portal.

- "The Flatland Role Playing Game" by Marcus Rowland (1998), revised and expanded as "The Original Flatland Role Playing Game" (2006).

- Lisa Randall, a theoretical physicist, gave a brief overview of Flatland in her book Warped Passages.

- Jasper Fforde asserts in his Thursday Next novel The Well of Lost Plots that the writing of Flatland used up the "last [pure] original idea".

- In the novel Snow Crash, Flatland is the remnant of the old Internet, which contrasts sharply with the photo-realistic 3-D environment of the Metaverse.

- In Larry Niven's Known Space science fiction series, the term "Flatlander" is slang, used by inhabitants of space, for people who have not been off Earth. This is said to be because, from any point on Earth, the world looks flat, while, from any point in space, inhabited worlds look round or jagged, but definitely not flat.

- The 2011 indie game "Flatland: Fallen Angle" developed by SeeThrough Studios is based on the central concepts of the novella.

[edit] See also

- Animal Farm, novella by George Orwell

- Blind men and an elephant

- Dimension

- Sphere-world

- Triangle and Robert

- The Dot and the Line

[edit] References

- ^ Abbott, Edwin A. (1884). Flatland: A romance in Many dimensions. Dover thrift Edition (1992 unabridged). New York, p. ii.

- ^ Abbott, Edwin A. (1884) Flatland, Part II, § 20.—How the Sphere encouraged me in a Vision, p 92

- ^ Abbott, Edwin A. Flatland: A romance in Many Dimensions. (1992, Page 25). Dover thrift Edition (unabridged). New York.

- ^ Stewart, Ian (2008). The Annotated Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. New York: Basic Books. pp. xvii. ISBN 0-465-01123-3.

- ^ "Flatland Reviews". http://www.math.brown.edu/~banchoff/abbott/Flatland/Reviews/index.shtml. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- ^ a b Stewart, Ian (2008). The Annotated Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. New York: Basic Books. pp. xiii. ISBN 0-465-01123-3.

- ^ "Flatland Reviews - Nature, February 1920". http://www.math.brown.edu/~banchoff/abbott/Flatland/Reviews/1920nature.shtml. Retrieved 2011-04-02.

- ^ Flatland at the Internet Movie Database

- ^ "DER Documentary: Flatland". http://www.der.org/films/flatland.html. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Flatland Animation: The project". http://flatlandanimation.blogspot.com/2011/05/project.html. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Flatland the Film". http://www.flatlandthefilm.com. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ^ "Flatland the Film". http://www.flatlandthefilm.com/. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ^ "Flatland: The Movie". http://www.flatlandthemovie.com. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. pp. 1. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.

[edit] External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Flatland |

[edit] Online and downloadable versions of the text

- Flatland, a Romance of Many Dimensions (first edition) on Wikisource

- Flatland, a Romance of Many Dimensions (second edition) on Wikisource

- Flatland at Project Gutenberg, text, no illustrations

- Flatland at Project Gutenberg (with ASCII illustrations)

- Flatland, a digitized copy of the first edition from the Internet Archive.

- Flatland, Second Edition, Revised with original illustrations (HTML format, one page)

- Flatland, Fifth Edition, Revised, with original illustrations (HTML format, one chapter per page)

- Flatland, Fifth Edition, Revised, with original illustrations (PDF format, all pages, with LaTeX source on github)

- Flatland audio book (mp3 format from Librivox)

- Flatland on Open Library at the Internet Archive

- "Sci-Fri Bookclub" recording of National Public Radio discussion of Flatland, featuring mathematician Ian Stewart (Sept. 21, 2012)

| ||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment