Ref Psychology Today Blog

Key points

- The reductionist physicalist position entails that phenomenal consciousness does not exist.

- Scientists increasingly realize that phenomenal consciousness can't be explained by the workings of the brain.

- For idealism, subjectivity undeniably has primacy when it comes to knowledge about ourselves and the world.

- For dual-aspect monism, consciousness and the brain are two different aspects of a same underlying reality.

Friedrich Nietzsche, in his book The Gay Science (Die fröhliche Wissenschaft), has a madman exclaim on a market square: “Whither is God? … I will tell you. We have killed him—you and I. All of us are his murderers.” At the market are many who do not believe in God and who laugh at the madman who carries a lantern on a bright morning. What Nietzsche wanted to convey with this is that the people at the market have not understood the consequences of what it means to live without God. According to the madman, we stray through infinite nothingness. And people have not realized it.

Often, when I read a text on the question of consciousness by defenders of physicalism, especially reductive physicalism, this passage of Nietzsche comes to my mind. In essence, physicalism boils down to the idea that only matter matters if we want to understand the behavior of humans. In principle, as many neuroscientists and philosophers alike have proclaimed, our thoughts and feelings are solely explainable by neural processes. To study the workings of the brain is all you need in order to describe what makes as humans. I have the feeling that those neuroscientists and philosophers consider themselves new Nietzsches, fearless avant-garde thinkers who communicate a truth to unenlightened people: as movements of charged ions and neurotransmitters we are infinite nothingness.

The reductionist physicalist position entails that what is primarily and immediate to every person—phenomenal consciousness—does not exist. This has led the philosopher Galen Strawson in an article to quote thinkers from antiquity to psychologist and Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman: “We know that people can maintain an unshakable faith in any proposition, however absurd, when they are sustained by a community of like-minded believers." According to Strawson the “most remarkable episode in the history of human thought" is that those believers deny the existence of something that everyone knows with certainty to exist: conscious experience, a first-person phenomenal perspective. Other physicalists at least acknowledge that we are conscious beings, but that phenomenal consciousness is “produced” by the brain. Future knowledge of how neural signals generate consciousness will for sure explain subjectivity – from a purely neurobiological standpoint. The unsolvable problem here is, however, that 'neurobiological processes' and 'subjective experience' stem from different, even if correlated, knowledge frameworks. The liver produces bile in order to turn fat into energy. Within the biological framework liver produces something. The brain cannot produce consciousness because subjective experience is not something that is part of a biologically measurable mechanism. The sentence that ‘the brain produces consciousness’ is a category mistake.

But perhaps physicalism is dead and we have not yet noticed? There are several contemporary madmen who proclaim the death of physicalism. In a recent post, I wrote about the movement of the romantics who thought outside the box in order to understand consciousness. In more recent years, there has been a similar movement in the sciences of consciousness. As an example, a prominent neuroscientist, Christoph Koch, now favors a modern version of panpsychism: the idea that the mind is an omnipresent feature of reality and therefore must be present throughout the universe.

So, what are the contemporary alternative standpoints? The absurdity of self-denial, the denial of phenomenal consciousness, is contrasted in a form of idealism which proclaims that consciousness is all there is. Phenomenal subjectivity has undeniable primacy when when it comes to knowledge about ourselves and the world. Consciousness comes first. In the conceptualization of philosophical idealism, following Immanuel Kant, one could say that the experienced world is a representation of the outside world. We do not have direct access to this world. In a modern form, this idea, as formulated by Bernardo Kastrup (2024), comes under the name of analytic idealism. There is thus no matter? According to this stance: No. What might seem as absurd at first glance becomes more convincing when we realize that what we call the external world is my experience of that world. The physical world is created through observation with our senses. Of course, the sense organs are also part of the alleged outside world—the eyes and ears in my head. However, these biological structures are also my experiences. Turning the perspective around: The claim that everything is experience seems more convincing than the claim that we do not have conscious experience at all and that everything is matter.

It is a fact that even hard-nosed researchers who ignore a potential phenomenological analysis of experience nevertheless still have to rely on the subjective experience of their human participants. In experimental settings participants have to somehow convey their subjective experience—for example, by pressing buttons for “seeing” certain targets. To accommodate this fact, experimental psychologist Max Velmans (2009) has introduced the notion of reflexive consciousness. For an understanding of consciousness we need both the first-person and the third-person perspectives as complementary frameworks. Together with the third-person perspective, the inherently personal and subjective experience is naturally complementary knowledge for any researcher of consciousness.

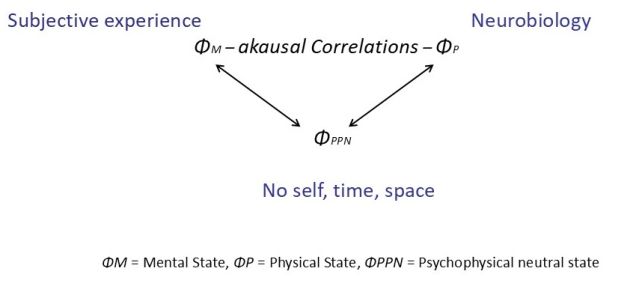

A more radical step forward is the conceptual idea of dual-aspect monism. This idea can already be found in the writings of philosopher and romantic F.W.J. Schelling. It is also the basis of the Pauli-Jung conjecture, stemming from the dialogue of the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Wolfgang Pauli and the psychiatrist C.G. Jung. Dual-aspect monism has recently been formulated in contemporary scientific terms by the physicist Harald Atmanspacher and the philosopher Dean Rickles (2023). According to dual-aspect monism, consciousness and the brain are two different (dual) aspects of the same underlying (one, undivided) reality. Mind and matter are based on a useful, pragmatic distinction but essentially can be traced back to a neutral structure, a fundamental reality in the background, which is neither mind nor matter. According to the Atmanspacher-Rickles model (schematized in the Figure above) both neurobiological processes (ΦP) and correlated subjective experience (ΦM) arise from an undivided reality ΦPPN. Note that in conventional physicalist concepts, ΦP (neurobiology) produces the state ΦM (subjective experience). "Somehow" consciousness arises from matter. In contrast, according to dual aspect monism, mind and matter are caused by an underlying neutral structure.

This psychophysically neutral and basic reality is inexpressible. It is not bound to the usual time-and-space structure, which only arises in the separation of experiential and physical reality, i.e. the generation of subject and object. The correlations between consciousness (ΦM) and neurobiology (ΦP) are unidirectional manifestations of ΦPPN. These correlations can be measured physiologically; for example, when the subjectively felt joy about an event occurs together with a bodily reaction (say, an increased pulse rate). These correlations are in principle predictable. An emotionally felt state of excitement is accompanied by certain physical activities. Or, as shown in my own research, our intrinsic ability to sense the passage of time correlates with activity in the insular cortex, which is the primary region of the brain to process body signals. These examples relate to the everyday correlative reality of body and mind. Note that in referring to the physical, I explicitly refer to the body and not just to the brain. The brain is embedded in the interwoven system of the whole body.

More and more people realize the absurdity of the extreme version of physicalism: Consciousness does not exist. Scientists are also increasingly realizing that, in principle, it is not possible to explain how phenomenal consciousness is “generated” or “produced” by the brain. There is movement on the scene. The above-mentioned alternative concepts of what subjective experience means might as well feel strange at first sight. At least we are out of an ideological deadlock. We are being freed to think out of the box to comprehend what consciousness might mean to us humans.

References

Atmanspacher, H., & Rickles, D. (2022). Dual-aspect monism and the deep structure of meaning. New York, London: Routledge.

Kastrup, B. (2024). Analytic idealism in a nutshell. London: iff Books.

Strawson, G. (2019). A hundred years of consciousness: “a long training in absurdity”. Estudios de Filosofía 59, 9–43.

Velmans, M. (2009). Understanding consciousness. Hove: Routledge